PeepShow & Tell: Sex in Archives Blog Post # 2 -

Academic Value of Archiving Sexuality: Discussion of University of Toronto's Sexual Representation Collection with Archives Director Patrick Keilty

For the next few weeks, we at the ACA McGill University Student Chapter invite you to join us for an immersive series of blog posts titled PeepShow and Tell: Sex in Archives. Through interviews with researchers and professionals working firsthand with explicit materials, we hope to illuminate the intrinsic value of sex and sexuality within the field of archiving and why these materials deserve to be preserved.

For this post, we spoke with Patrick Keilty, Associate Professor in the Faculty of Information and Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies at the University of Toronto. He is also the Archives Director of the Sexual Representation Collection (SRC), administered by the Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies. Professor Keilty's research pertains primarily to the politics of digital infrastructures in the sex industries and the materiality of media in erotohistoriography (Patrick Keilty, n.d.).

Jay: The creation of sexually explicit imagery has been a long-performed activity across cultures and periods throughout human history. While this imagery has always existed, the concept of pornography and its implied immorality and impropriety is a modern and western concept (Barriault, 2009, p.221). Even after the sexual revolution of the 1960s, within the western world, we continue to hold bias and discomfort with sex and sexuality and, by extension, are biased towards preserving sexually explicit materials (Barriault, 2009, p.222). In his article Hard to Dismiss, Barriault presents, through case study analysis, the research value of gay male erotica and pornography. He argues that sexually explicit materials are not only materials for pleasure and titillation (which is valuable in itself) but worth archiving as their value extends beyond their original creation by giving a glimpse into a person's lived experiences, a community, or a subculture (Barriault, 2009, p.222).

.jpg)

Through correspondence with Professor Keilty, we investigate the academic and cultural value sexuality-focused archival collections can provide, and we discuss the unique challenges of working with sexually explicit materials, the responsibilities of archivists to these materials, the best parts of working with these kinds of collections and what's on the horizon for the SRC.

Jay: Could you tell me a little more about the creation of the Sexual Representation Collection and your role as Archival Director?

Prof. Keilty: Administered by the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, an academic unit within the University of Toronto, Sexual Representation is one of Canada's largest collections of sex work history and adult film history. Professor Emeritus Brian Pronger started SRC informally but intentionally in the late 1980s to support his research. After writing a book about masculinity and homosexuality in sports culture, he began to research commercially produced gay cis male pornography. Under the stewardship of subsequent Archives Directors Mariana Valverde and Nick Matte, the SRC expanded its holdings with a particular focus on feminist, queer, trans, and kink sexual cultures.1

In 2018, a new Director of the Bonham Centre, Prof. Dana Seitler, asked me to be the SRC's fourth Archives Director as part of my administrative service at the Centre. I oversee all custodial and archival tasks related to the collection, administrative responsibilities, reference and liaison work. I am especially indebted to my current crop of research assistants (RAs), work-study students, and interns: A. Hawk, Maggie MacDonald, Camille Intson, Gillian Wall, Asha Chiraghdin, Lo Humeniuk, Sydney Perkins, Roxy Moon, and Ty Murphy. I am very fortunate to work with such an exceptional team!

Jay: Do you find that the sexually explicit content of the collection creates any unique archiving difficulties compared to less erotically charged records? Prof. Keilty: The funniest policy UofT administrators imposed on us is "no topless boxes" when materials circulate within the university. Administrators don't want anyone inadvertently "exposed" to sexual content for fear it might legally constitute sexual harassment. Certainly, we need to be careful about the kinds of sensory demands we put on people, but that policy also assumes something shameful about histories of sex, sexuality, and pleasure. That administrators use the phrase "topless box," is hilariously ironic given the nature of the collection. The irony is lost on them. I plan to write a paper about how a "topless box" is a site for creative irruption in the archive. As for the specific challenges of archival arrangement, Liana Zhao, the Director of Library and Special Collections at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University, has written about the unique challenges there for organizing and describing sexually explicit content.2 More substantively, the SRC is especially careful about our digitization efforts. In some cases, our materials fall under Public Domain in Canada. Digitization for scholarly or preservation purposes falls under the terms of the "Libraries, Archives, and Museums" exceptions in section 30.1 of Canada's Copyright Act. Unlike the United States, Canada lacks an orphan works regime. When determining whether to disseminate third-party copyrighted material without restrictions, we rely on Simon Fraser University's "Risk Management Copyright Policy Framework for SFU Library Digitization Projects" (2016), which represents the gold standard of copyright guidelines for library and archival digitization projects in Canada. We simply take this policy and enhance it with our own values about honouring sex work. Beyond copyright, the SRC has an ethical obligation to obtain creator and performer consent, if still alive, before making materials openly accessible online. In cases where we are unable to determine copyright or where we are unable to obtain creator and performer consent, the SRC makes the materials available to scholars through a secure online platform, protected behind a university-administered firewall. Providing archival and scholarly access to copyrighted materials behind a firewall is critical for maintaining the SRC's trust and faith with members of the sex industries, who are also some of our donors. It is critical to honouring sex work as work, a central ethical premise at the SRC. We let scholars know about any restrictions upon request, in our finding aids, and on our website.

|

Jay: What are your favourite parts of your job working with these records? Prof. Keilty: I love working with smart, intellectually curious queer and trans students, who always bring a lot of thoughtfulness and energy to the job. I am endlessly impressed with their dedication, ability to work as a team, and enthusiasm for the collection. As queer and trans students, they have a personal investment in a collection that provides a portal into the histories of pleasure and erotic ways of knowing about the past. They are not interested in embracing the archive as a site for historical accumulation. Instead, they recognize it as a site of creative irruption, one that re-assembles erotic histories to serve as the contestatory ground over the boundaries of sex. I love thinking with them about what gets absented from a collection as a "bad,” "risky," or unarchivable object. We grapple with the problems and pitfalls in the task of curation and knowledge production when sex is the object.

|

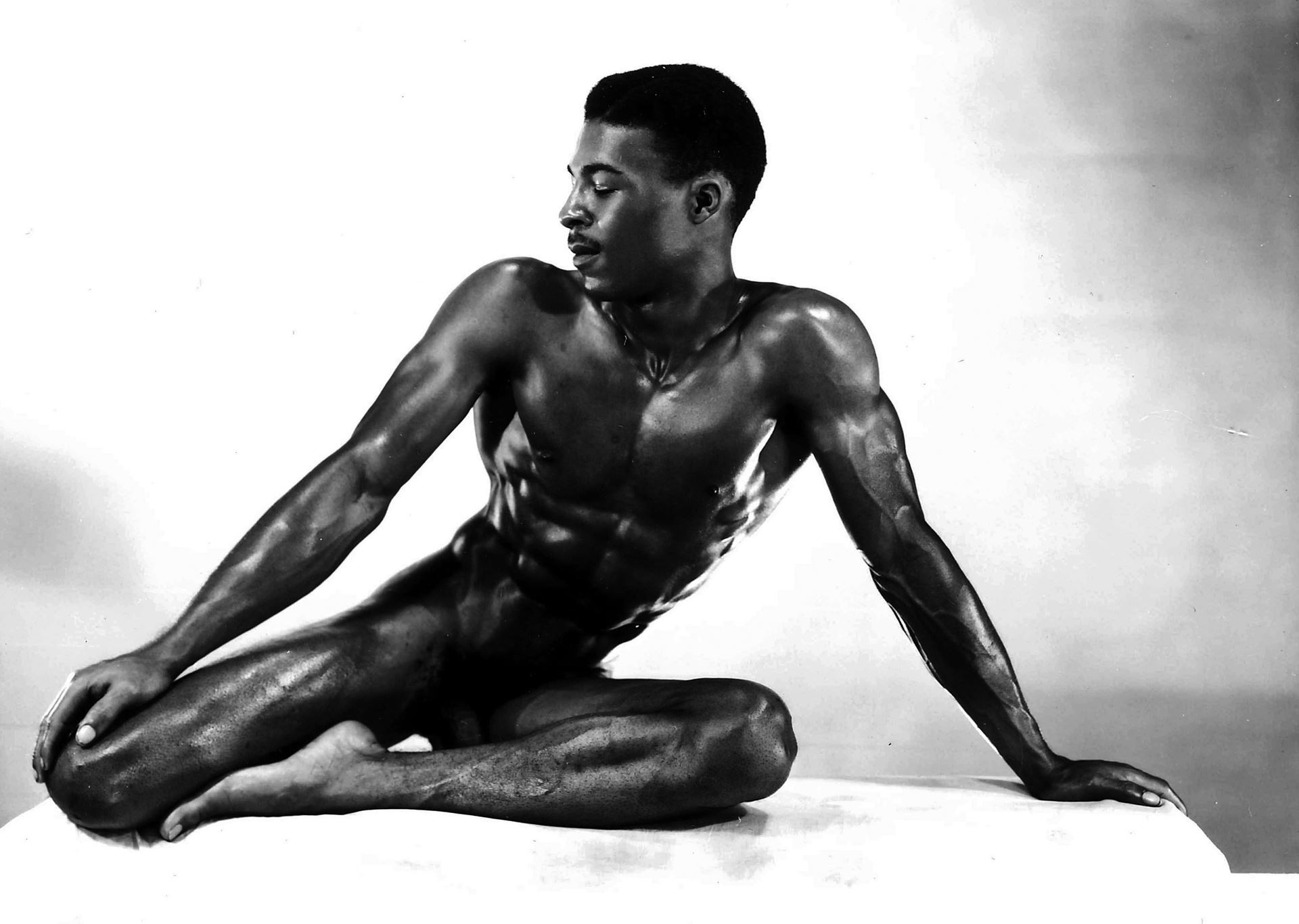

Jay: What are the most requested materials or collections? Prof. Keilty: The collection that most scholars ask to see is the Erotic Film Collection.3Our most recent acquisition, film historian Tom Waugh's collection, served as the primary source material for much of his research and teaching, including 1,300 films and videos of queer cinema and AIDS-era gay cis male pornography from the United States and Canada, including a particularly strong collection of Montréal queer cinema and pornography. The highlight of his collection is the nearly 6,000 photographs and negatives, including rare beefcake photographs from the 1950s and 1960s featuring BIPOC models. The history of beefcake could be rewritten based on this collection alone. Lots of scholars also seem to request the papers of the Canadian Coalition Against Customs Censorship (CCACC), an activist group in the 1980s and 1990s that influenced changes in Canadian laws and culture. We fully digitized the collection and published it on the Internet Archive. Finally, I love that the Annie Sprinkle and Lord Morpheous collections contain things like dildos, leather harnesses, and special rope for BDSM play. That's always a highlight of any tour!

|

Jay: What do you think the collection is missing? Prof. Keilty: It's important to recognize that the SRC originated as an academic archive, founded by a white gay cis male professor. Pronger's acquisition practices largely reflect that perspective. Starting with Archives Director Nick Matte, a trans man, the SRC began to expand its collections to include more global, trans, and non-binary histories. I would especially like to expand our collection to include more "queercrip pornography" (a phrase from Loree Erickson, a disability advocate and Toronto-based queercrip porn maker).4However, I also recognize that some records will never be recovered. We cannot fully rectify archival erasure. Nevertheless, we need to take active steps to ensure that forms of systemic erasure do not continue in the future. Jay: Any interesting projects underway or new additions to the collection we can look forward to? Prof. Keilty: Right now, we're having fun digitizing parts of our collection for the Adult Film History Project on the Internet Archive. I am excited to see my RA Gillian Wall process and describe Tom Waugh's collection by the end of the summer. Eventually, I want to re-connect with the University of Toronto Libraries about creating records for our collection in their online catalog. We started that discussion before the pandemic, but it had to be postponed. I am looking forward to an exhibit of early erotic moving images, curated by two of my RAs, Maggie MacDonald and Camille Intson -- scheduled for display at the Faculty of Information at the University of Toronto in August – September 2022. Finally, I am preparing an exhibit with Prof. Mireille Miller-Young (UCSB) and Nguyen Tan Hoang (UCSD) of photographs from Mireille's Black Erotic Archive, the University of South Florida's Asian Male Nude Collection, and the SRC's Tom Waugh Collection. Stay tuned for that in the coming years! Jay: The SRC is a great example of a collection being built out of necessity to mitigate an existing gap in research materials.Having often been left out of the larger institutions, marginalized communities have taken it upon themselves to preserve their histories. As noted by Tang in the Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable's Lavender Legacies Guide, this brought the creation of grassroots archives to fill the silences created by dominant historiography narratives found in most archives (Tang, 2017, p. 445.) What's uniquely interesting about the SRC is that while it necessitated a grassroots approach in its creation, it has become a formal institutional collection. |

We hope this blog and the whole PeepShow &Tell series encourage readers to reflect on the importance of collecting sexually explicit records.” To learn more about the SRC and its upcoming projects, checkout their Instagram page @sexualrepresentationcollection and website https://sds.utoronto.ca/sexual-representation-collection/ Jay Bossé, the co-author for this piece, is a graduate student with the School of Information Studies at McGill University and Co-Coordinator of the ACA McGill University Student Chapter Blog Series PeepShow & Tell: Sex in Archives. Bibliography Barriault, M. (2009). Hard to Dismiss: The Archival Value of Gay Male Erotica and Pornography. Archivaria, 68, 219–246. Patrick Keilty. (n.d.). University of Toronto. Retrieved March 24, 2022, from https://ischool.utoronto.ca/profile/patrick-keilty/ Tang, G. (2017). Sex in the Archives: The Politics of Processing and Preserving Pornography in the Digital Age. The American Archivist, 80(2), 439–452. Images courtesy of Patrick Keilty and the Sexual Representation Collection.

|

Our Community

| Public Awareness & Advocacy

| Resources

| Submissions

|

Contact Us

Suite 1912-130 Albert Street

Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5G4

Tel: 613-383-2009

Email: aca@archivists.ca

The ACA office is located on the unceded, unsurrendered Territory of the Anishinaabe Algonquin Nation whose presence here reaches back to time immemorial.

Privacy & Confidentiality - Code of Ethics & Professional Conduct

Copyright © 2023 - The Association of Canadian Archivists